|

Have had a wonderful variety of operatic experiences recently and, while I’m always interested in the insights that different productions can bring to a work, I can’t help but reflect chiefly on the quality of the music-making and, even more, on how the composer problem-solved, setting text and underlining a drama by means of the singing voice. While not denying the cast and creatives their credit, nothing can redeem a bad score - whereas a good score can suffer if justice isn’t done.

0 Comments

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document. Your Editorial "The Guardian view on touring opera: thwarted in its mission to bring music to the people" (10 November) misses a vital point. The trouble with 'opera' is that it’s obsessed with a small canon of works almost exclusively from the 18th and 19th centuries. Exceptions are few and far between, while contemporary works, with their inherent risk, are as rare as hen’s teeth. And so opera isn't just perceived as elitist and expensive (mistakenly) but also as 'uncool' and irrelevant, especially by the young.

Scaled-down versions of those classic favourites don't come anywhere near an authentic experience and touring them has limited effectiveness in growing audiences. Those of us further down the ladder attempting to mount new opera on a very small scale face a huge battle with conservative audiences, limited funding (no encouragement from the Arts Council there) and apathy from colleagues and influencers in the industry: all seem to be stuck in the operatic past. Without a sustained and sustainable renewal of the genre, however, the myth of opera's obsolescence will become a reality. So we need more lithe and nimble regional touring companies which can afford to mount new operas and thereby enhance cultural life more widely - and in more senses than one. It's perhaps the Royal Opera's Linbury Theatre, with its varied offerings of opera and dance, new and old, which could and should plant regional off-shoots. ENO should stay put. www.theguardian.com/music/2023/nov/13/its-a-shame-that-opera-remains-stuck-in-the-past https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/nov/10/the-guardian-view-on-touring-opera-thwarted-in-its-mission-to-bring-music-to-the-people? GELLER INSTITUTE OF AGEING AND MEMORY

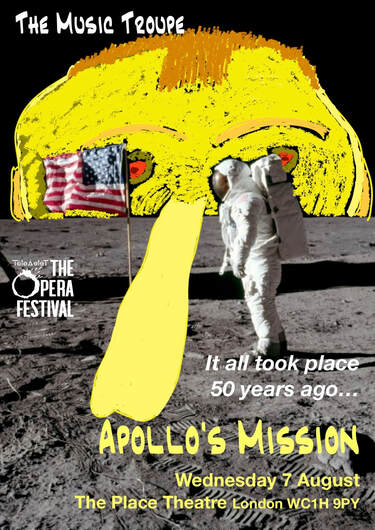

Dementia Friendly Opera – The Last Siren Date: 30th August 2023 Location: Lawrence Hall, St Mary’s Road Campus by Dr. Andy Northcott, Senior Lecturer in Sociology of Medicine, University of West London Dementia Friendly Opera is a collaboration between the Geller Institute of Ageing and Memory (GIAM), the London College of Music (LCM) and The Music Troupe. From the performance we hope to develop and refine a toolkit for putting on Dementia Friendly Opera and Dementia Friendly Performance at venues across the country, particularly those underserved by the Arts and for whom attendance at such events would require arduous planning and travel, laying the foundations for work beyond the London College of Music and The Music Troupe, allowing any production to become accessible and dementia friendly. It seems to me, the year begins anew after the shortest day. However, with all the reflections on FB today, I’ll throw in my thoughts on a busy and peculiar year of musical composition. This time, 12 months ago, I was working on Swellfellow the Tyrant, an obscure political satire by Shelley which could hardly have turned out more topical and relevant in the light of the subsequent Tory machinations. Written for a local opera group which then failed to grasp the nettle, they thought it wasn’t popular enough to rustle up support. A foolish sentiment, in my opinion, as opera won’t thrive going forward unless the repertory is renewed with small-scale, entertaining but relatively economical works. An opportunity lost to work in the local community. And so, straight on to write The Burning Question for young Norman Welch which didn’t start off with the idea that the dead pope should be female, but that’s how it landed up. It went down pretty well at the Tete a Tete Opera Festival in the summer - lots of young people there - and, as I write, there are plans to revive it soon. Probably the best team effort I’ve enjoyed working on: it’s so satisfying (and flattering) to see a talented cast throw themselves into something you’ve written. Four months later, and another piece is finished: Masque of Vengeance, this time a Jacobean tragedy, a bloodbath in which most of the comparatively large cast are slaughtered by the end. I really must try and understand why, after Elizabeth’s death, this genre of revenge tragedy flourished. Wait! I meant Elizabeth I…! And in between we released the film of Last Party on Earth, which we shot live on a set and on location during lockdown. There aren’t many opera films other than relays of house performances, so thanks to Korina Kokali et al. for the inspiration. All things considered, some steps in the right direction this year: as one acorn said to another, we may be small but we’ll give it a go!

Mark Wiggleworth’s suggestion (The Guardian, 10 Nov 2022) that English National Opera should seek a new state-of-the-art lyric theatre is spot on. The trouble with the recent debates over the future of English National Opera has much to do with the term ‘opera’ covering over 400 years of works that come in all forms, shapes and sizes. For much of that time, companies and the houses that accommodated them, were smaller and more intimate. Some of us mourned when Sadler’s Wells Opera moved to the Coliseum in 1968 in order to expand into the Wagner/Puccini/Richard Strauss repertory, for in large spaces something is lost when performing works of previous periods. While applauding ENO’s many great achievements since then, particularly as a showcase for U.S. composers, a retreat into a smaller, purpose-built venue in London could see it flourish as a complementary company to the Royal Opera rather than one competing with it. Smaller productions would be more suitable for touring, too. There is also an important point to be made about the future survival of opera: the repertory must be renewed with contemporary works in sufficient quantity to allow new creative talent to flourish. This is much more likely to happen in a small-scale environment.

Orpheus at Opera North: greater than the sum of its parts

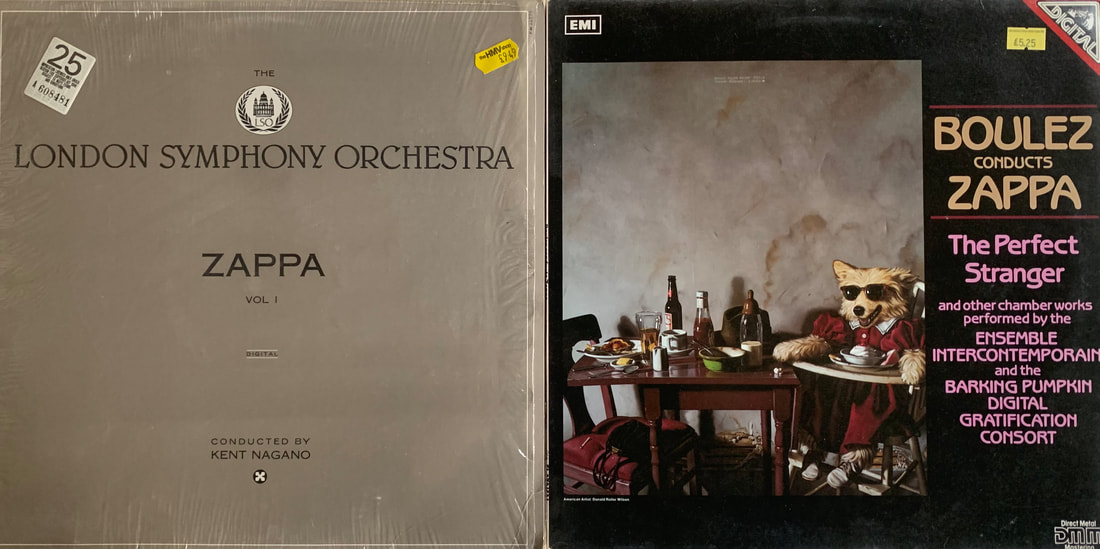

(Grand Theatre, Leeds, Thursday 20 October 2022) The myth of Orpheus was fundamental to the history of early opera: Peri’s Euridice is the earliest surviving opera and its performance in Florence in 1600 was attended by the Duke of Mantua - Monteverdi’s employer - and Alessandro Striggio, who would write the libretto for Monteverdi’s opera of 1607. The attraction of the myth, of course, was that the story was widely known and understood; Orpheus, as a musical practitioner, becomes a parable for the genre of opera itself, a union of words and music which gives voice to this drama about love and loss. No wonder composers have struggled with the myth’s ending, sometimes tragic, sometimes happy, and sometimes, as with Monteverdi’s later drafts, somewhere in between. Watching the Zappa biographical documentary yesterday brought to mind the occasion when, on 11th January 1983, I made my way over to the Barbican, London in the hope of getting a ticket to Frank Zappa's concert with the LSO. It was sold out, and there was already a long queue for returns by the time I got there. But I was on my own, I remember, and I thought I stood a chance of someone not turning up at the last minute. The audience made their way into the auditorium; people in the returns queue gave up and dispersed, but I persevered. Then the miracle happened: not only was I approached with the offer of a ticket - you had to be wary of touts - but it was a comp! 'It's fine', the guy said, 'I'm a roadie!' I got one of the best seats in the house sitting amongst members of Zappa's team.

A shout out to the Youth Orchestra “Il mosaico” from the St. Gallen area of Switzerland. It’s been in existence for many years and by 2000 it was acknowledged as the leading youth symphony orchestra in the country. I caught them at a recent concert in Cortona, Italy (28 May 2022) in the beautiful surroundings of the deconsecrated church of San Agostino as part of an Italian tour that had been arranged to replace one to Ukraine.

Having never taken to cinema relays, the experience of watching opera at home has been better than I would have imagined, (albeit at the mercy of an internet connection). Think of some of the advantages: (1) No travel involved, no late-night trains home. (2) Cameras get in on the action, close up, saving hundreds on the cost of a front stalls ticket. (3) No irritating audience neighbours. (4) Watch in comfort when you feel like it. (5) Subtitles rather than surtitles. (6) Rewind as required. (7) Truly international viewing. (8) Excellent sound, voices clearly audible. (9) Participate in watch party chats. Of course, the thrill of experiencing a live-performance in-house is lacking, but so are the chances of contracting the virus. Watching great opera while also staying alive: a no-brainer!

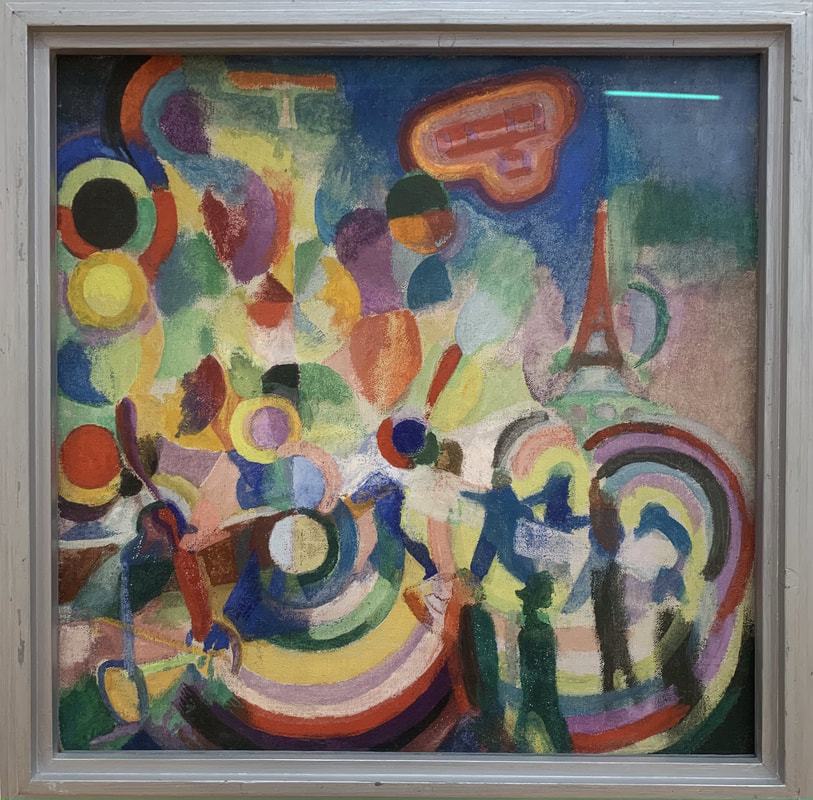

How will new viewing habits affect the future of opera? Since it receives taxpayers' support, It seems only right that the Royal Opera, for example, makes available its output for all to see, regardless of geography . So will there be a two-tier audience? Theatre attendees paying lots to be there while those at home watch for free? How about an annual subscription for the UK's output of opera made available on a special channel? Or does this new situation herald the demise of grand opera houses altogether? I've just finished a short piano concerto. The orchestral accompaniment is strings only - could be single strings, too. I wanted the piano and strings to work together rather than have the pianist stand out as a celebrity, so I called the solo part 'piano continuo' since it plays all the time. I know one of my many weaknesses is that after a couple of minutes I go from one thing to another; the result here is a kind of suite of pieces which may feel disjointed; of course, they're meant to complement each other like a multi-course meal. In fact, there are connections running through the piece and it's technically written as one movement, so I hope it will have some coherence . This Kandinsky in Grenoble sort of looks what it sounds like, to me at any rate.

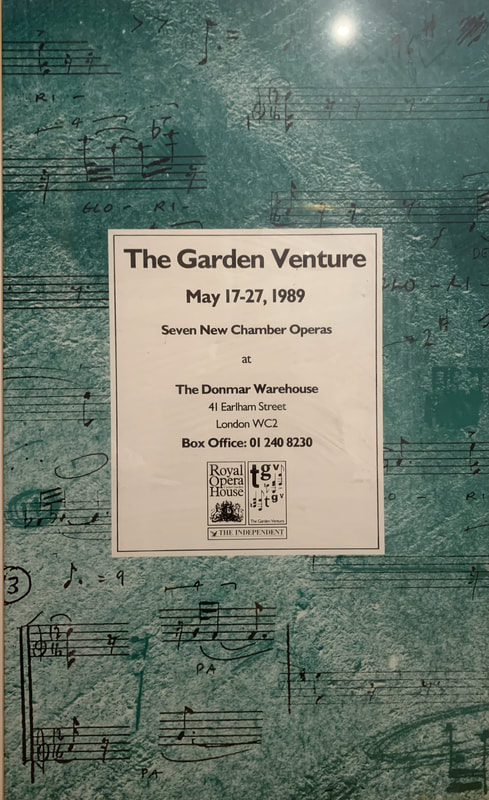

edwardlambert.co.uk/instrumental.html#pianoconcerto The recent death of Andrew Sinclair, international opera director, has suddenly brought to mind the period when he and I most closely worked together. The occasion was his direction of my chamber opera Caedmon, produced by The Garden Venture at the Royal Opera House in 1989. Small-scale opera is a thing nowadays, not surprising given the economies involved. Lots of popular classics have been doing the rounds - La Boheme, Carmen, La Traviata, G&S, etc., as well as arrangements of less mainstream works. Anything to get opera out and about and attract new audiences everywhere is to be greatly applauded. But it has to be admitted the resulting musical experience without orchestra and choruses is likely to be underwhelming compared to the experience that was intended. Just as we like ‘Early Music’ to sound right with period instruments, so grand opera ideally needs to be savoured as the ‘real thing’, performed by the forces and in the spaces it was written for. But it’s worth noting that theatres in the 17th and 18th century (1000 seats) were nowhere near as large as those built in the 19th century (around 2000 seats) - and these are dwarfed by the monster new-builds and extensions of the 20th (3000 to 4000 capacity). In these auditoria, most spectators are distant from the stage, many spy on the performance through opera glasses and typically listen with acoustic enhancement (amplification) even if they’re not aware of it. By contrast, small-scale opera in intimate venues allows the audience to feel close to the stage and feel more involved in the drama. Clearly, voices don’t need to be so large (and wobbly) and don’t have to strain; they can, more often than not, sound more detailed and beautiful. The challenge we face, therefore, is to create new, tailor-made, small-scale works that appeal to audiences everywhere and enhance the repertory of sung dramas that are so powerful and compelling.

Last night was aired one of the best TV arts programmes I've watched in recent years. It was like something from the good old days when the BBC took risks, rose to its subject matter and didn't dumb down to an audience only thought to be interested in cake-baking, auctions or murders. Guardian review.

I’ve just finished reading The Man Without Qualities by Robert Musil. I'm doubtless late to the party but just in case there’s someone reading this who hasn’t yet got around to dusting down this hefty tome, let me explain that Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften is widely regarded as one of the world’s great novels, compared by some to Ulysses or The Remembrance of Things Past (The Times). No doubt it is something of a cult work in German-speaking lands.

A project in the autumn and winter lockdowns recently has been to finish another Lorca setting. My operatic version of Así que pasen cinco años I've called In Five Years' Time, which seems a more natural translation than 'When Five Years Have Passed'. Death is a theme of the play and very much in the headlines right now.

About a year ago I finished this chamber opera on a play by Oscar Wilde. I was keen to write an Italian-style opera although never sure what I meant by that.

Written before the pandemic outbreak, this could hardly have been more timely. A rhyming libretto by Leo Doulton at first had me stumped: how could such a doom-laden scenario be treated as a 'comedy of manners', as he put it?

|

Edward LambertComposer and musician Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

|

Scores available by means of a Performance Restricted license from IMSLP

The Music Troupe

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed