|

Have had a wonderful variety of operatic experiences recently and, while I’m always interested in the insights that different productions can bring to a work, I can’t help but reflect chiefly on the quality of the music-making and, even more, on how the composer problem-solved, setting text and underlining a drama by means of the singing voice. While not denying the cast and creatives their credit, nothing can redeem a bad score - whereas a good score can suffer if justice isn’t done.

0 Comments

Your Editorial "The Guardian view on touring opera: thwarted in its mission to bring music to the people" (10 November) misses a vital point. The trouble with 'opera' is that it’s obsessed with a small canon of works almost exclusively from the 18th and 19th centuries. Exceptions are few and far between, while contemporary works, with their inherent risk, are as rare as hen’s teeth. And so opera isn't just perceived as elitist and expensive (mistakenly) but also as 'uncool' and irrelevant, especially by the young.

Scaled-down versions of those classic favourites don't come anywhere near an authentic experience and touring them has limited effectiveness in growing audiences. Those of us further down the ladder attempting to mount new opera on a very small scale face a huge battle with conservative audiences, limited funding (no encouragement from the Arts Council there) and apathy from colleagues and influencers in the industry: all seem to be stuck in the operatic past. Without a sustained and sustainable renewal of the genre, however, the myth of opera's obsolescence will become a reality. So we need more lithe and nimble regional touring companies which can afford to mount new operas and thereby enhance cultural life more widely - and in more senses than one. It's perhaps the Royal Opera's Linbury Theatre, with its varied offerings of opera and dance, new and old, which could and should plant regional off-shoots. ENO should stay put. www.theguardian.com/music/2023/nov/13/its-a-shame-that-opera-remains-stuck-in-the-past https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/nov/10/the-guardian-view-on-touring-opera-thwarted-in-its-mission-to-bring-music-to-the-people? It seems to me, the year begins anew after the shortest day. However, with all the reflections on FB today, I’ll throw in my thoughts on a busy and peculiar year of musical composition. This time, 12 months ago, I was working on Swellfellow the Tyrant, an obscure political satire by Shelley which could hardly have turned out more topical and relevant in the light of the subsequent Tory machinations. Written for a local opera group which then failed to grasp the nettle, they thought it wasn’t popular enough to rustle up support. A foolish sentiment, in my opinion, as opera won’t thrive going forward unless the repertory is renewed with small-scale, entertaining but relatively economical works. An opportunity lost to work in the local community. And so, straight on to write The Burning Question for young Norman Welch which didn’t start off with the idea that the dead pope should be female, but that’s how it landed up. It went down pretty well at the Tete a Tete Opera Festival in the summer - lots of young people there - and, as I write, there are plans to revive it soon. Probably the best team effort I’ve enjoyed working on: it’s so satisfying (and flattering) to see a talented cast throw themselves into something you’ve written. Four months later, and another piece is finished: Masque of Vengeance, this time a Jacobean tragedy, a bloodbath in which most of the comparatively large cast are slaughtered by the end. I really must try and understand why, after Elizabeth’s death, this genre of revenge tragedy flourished. Wait! I meant Elizabeth I…! And in between we released the film of Last Party on Earth, which we shot live on a set and on location during lockdown. There aren’t many opera films other than relays of house performances, so thanks to Korina Kokali et al. for the inspiration. All things considered, some steps in the right direction this year: as one acorn said to another, we may be small but we’ll give it a go!

Mark Wiggleworth’s suggestion (The Guardian, 10 Nov 2022) that English National Opera should seek a new state-of-the-art lyric theatre is spot on. The trouble with the recent debates over the future of English National Opera has much to do with the term ‘opera’ covering over 400 years of works that come in all forms, shapes and sizes. For much of that time, companies and the houses that accommodated them, were smaller and more intimate. Some of us mourned when Sadler’s Wells Opera moved to the Coliseum in 1968 in order to expand into the Wagner/Puccini/Richard Strauss repertory, for in large spaces something is lost when performing works of previous periods. While applauding ENO’s many great achievements since then, particularly as a showcase for U.S. composers, a retreat into a smaller, purpose-built venue in London could see it flourish as a complementary company to the Royal Opera rather than one competing with it. Smaller productions would be more suitable for touring, too. There is also an important point to be made about the future survival of opera: the repertory must be renewed with contemporary works in sufficient quantity to allow new creative talent to flourish. This is much more likely to happen in a small-scale environment.

Orpheus at Opera North: greater than the sum of its parts

(Grand Theatre, Leeds, Thursday 20 October 2022) The myth of Orpheus was fundamental to the history of early opera: Peri’s Euridice is the earliest surviving opera and its performance in Florence in 1600 was attended by the Duke of Mantua - Monteverdi’s employer - and Alessandro Striggio, who would write the libretto for Monteverdi’s opera of 1607. The attraction of the myth, of course, was that the story was widely known and understood; Orpheus, as a musical practitioner, becomes a parable for the genre of opera itself, a union of words and music which gives voice to this drama about love and loss. No wonder composers have struggled with the myth’s ending, sometimes tragic, sometimes happy, and sometimes, as with Monteverdi’s later drafts, somewhere in between. Watching the Zappa biographical documentary yesterday brought to mind the occasion when, on 11th January 1983, I made my way over to the Barbican, London in the hope of getting a ticket to Frank Zappa's concert with the LSO. It was sold out, and there was already a long queue for returns by the time I got there. But I was on my own, I remember, and I thought I stood a chance of someone not turning up at the last minute. The audience made their way into the auditorium; people in the returns queue gave up and dispersed, but I persevered. Then the miracle happened: not only was I approached with the offer of a ticket - you had to be wary of touts - but it was a comp! 'It's fine', the guy said, 'I'm a roadie!' I got one of the best seats in the house sitting amongst members of Zappa's team.

A shout out to the Youth Orchestra “Il mosaico” from the St. Gallen area of Switzerland. It’s been in existence for many years and by 2000 it was acknowledged as the leading youth symphony orchestra in the country. I caught them at a recent concert in Cortona, Italy (28 May 2022) in the beautiful surroundings of the deconsecrated church of San Agostino as part of an Italian tour that had been arranged to replace one to Ukraine.

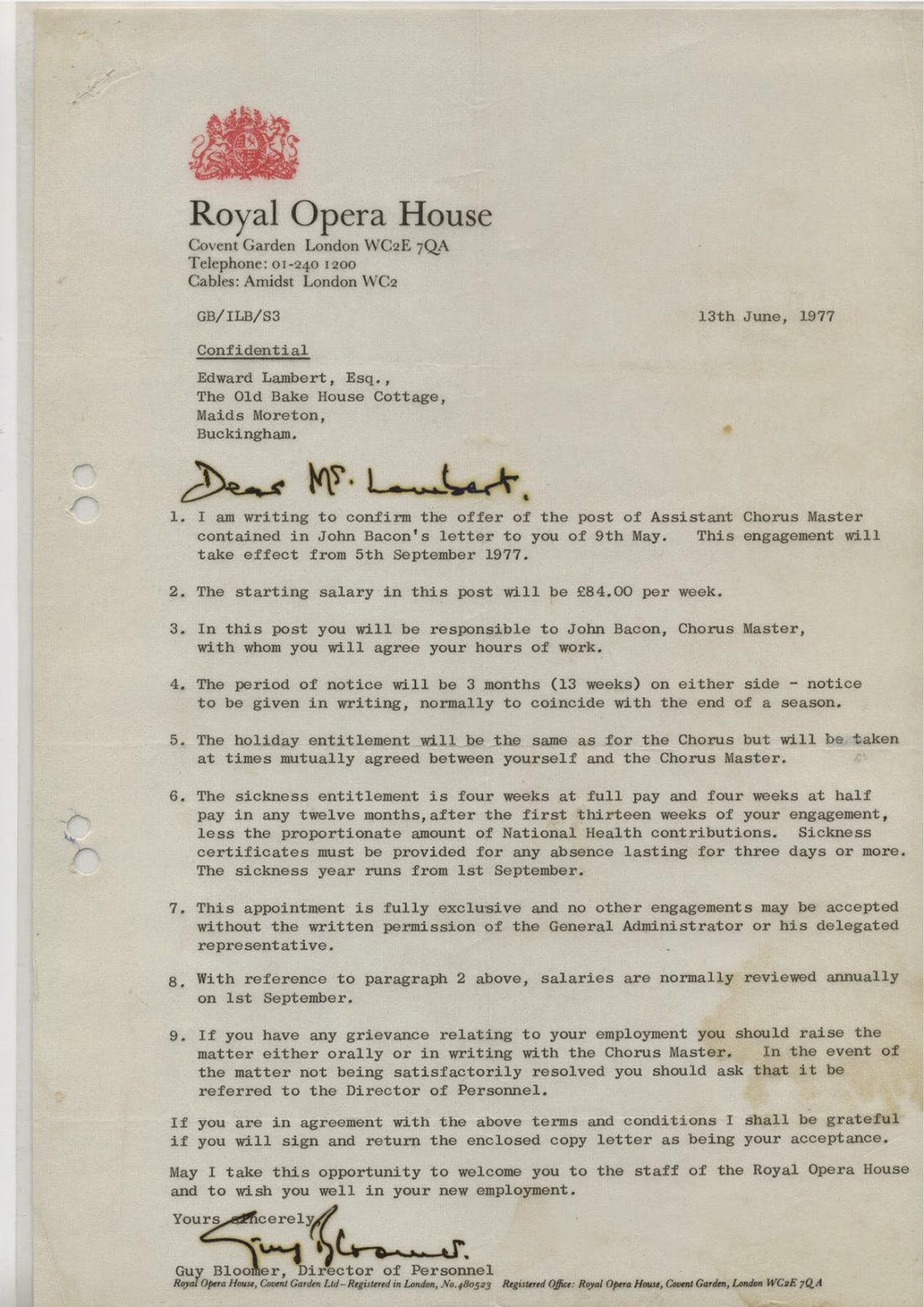

The recent death of Andrew Sinclair, international opera director, has suddenly brought to mind the period when he and I most closely worked together. The occasion was his direction of my chamber opera Caedmon, produced by The Garden Venture at the Royal Opera House in 1989. Small-scale opera is a thing nowadays, not surprising given the economies involved. Lots of popular classics have been doing the rounds - La Boheme, Carmen, La Traviata, G&S, etc., as well as arrangements of less mainstream works. Anything to get opera out and about and attract new audiences everywhere is to be greatly applauded. But it has to be admitted the resulting musical experience without orchestra and choruses is likely to be underwhelming compared to the experience that was intended. Just as we like ‘Early Music’ to sound right with period instruments, so grand opera ideally needs to be savoured as the ‘real thing’, performed by the forces and in the spaces it was written for. But it’s worth noting that theatres in the 17th and 18th century (1000 seats) were nowhere near as large as those built in the 19th century (around 2000 seats) - and these are dwarfed by the monster new-builds and extensions of the 20th (3000 to 4000 capacity). In these auditoria, most spectators are distant from the stage, many spy on the performance through opera glasses and typically listen with acoustic enhancement (amplification) even if they’re not aware of it. By contrast, small-scale opera in intimate venues allows the audience to feel close to the stage and feel more involved in the drama. Clearly, voices don’t need to be so large (and wobbly) and don’t have to strain; they can, more often than not, sound more detailed and beautiful. The challenge we face, therefore, is to create new, tailor-made, small-scale works that appeal to audiences everywhere and enhance the repertory of sung dramas that are so powerful and compelling.

I went to see Music Theatre Wales' production of The Golden Dragon in Basingstoke recently. This is a production which has caused some controversy because of its ‘yellowface’ casting.

Attended a performance last night of Le Grand Macabre at the Barbican, London. An immensely good performance and riveting from start to finish. It was great to have the London Symphony Orchestra on stage, which meant we could relish the score's fabulous textures which bristled and shimmered and hooted and blasted and everything in between.

The only chance I had recently of catching up with Julian Jacobson and Mariko Brown who have formed an exciting piano duo http://marikojulianpianoduo.com was to go to their rehearsal in Birmingham last week.

A single remaining, inexpensive amphitheatre seat tempted me to venture to Die Frau ohne Schatten at the Royal Opera House yesterday afternoon.

Recently attended an operatic relay from Royal Opera House in the local cinema. Heard much about these events and wanted to experience one for myself, but I have to admit I was dreadfully disappointed.

Although as a youngster I certainly wanted to write, I felt a pre-requisite of becoming a composer was a thorough knowledge of musical history and musical language. The study of harmony and counterpoint from medieval methods through to the serialists absorbed me until my mid-twenties - along with the process of becoming a musician.

We recently celebrated Verdi's 200th birthday. I arranged a kind of party in Newbury, invited locals to Come, Sing or Listen, and Drink. I might well have added Eat, since a beautiful cake was made in his honour. Verdi's not my favourite composer - I don't think I have a real favourite anyway - but I wouldn't have wanted to organise this occasion for anyone else. Verdi's special. You don't have to be a revolutionary to write good music. You don't have to adopt a musical language which is up-to-the-minute, or even avant-garde. You just have to write good music. And in Verdi's case, he wrote in a style which is so much his own that you can't mistake it for anyone else. Once he gets into his stride, he doesn't imitate anyone else. And no other composer sounds like him. Therefore that makes him individual.

Compare him to Wagner. Everyone started writing like Wagner. And if Verdi's heir is Puccini-cum-Wagner - well, then everyone started writing like Puccini, and Hollywood still does! The late Romantic style is common currency, a sort of Esperanto of music, to be consumed globally like MacDonalds! Verdi - not so. A rock-solid individual. I must catch up with some more operatic experiences this year: there was Glass' A Perfect American, whose music was much less absorbing than that of Akhnaten or Satyagraha and whose subject was not very interesting. If Walt Disney had no redeeming qualities, how was the opera going to yield any insights into the human condition? Apart from an entertaining production, the work itself seemed pointless.

Lohengrin in Cardiff was visually depressing - a nineteenth century prison? - but the music won out in any case. Brought back many memories of one of my first tasks at the Royal Opera House when I joined the staff there: coaching the chorus was hampered by constant strikes in those medieval, pre-Thatcher times and it was touch-and-go whether the music could be learnt in time. No such worries with WNO - the chorus were spectacular and so were the cast and orchestra. The clarity and directness of the music when performed well like this are very refreshing in comparison to Wagner's later works. Wagner Dream by the late, great Jonathan Harvey was, unfortunately for me, impenetrable. Multi-layered, complex and very dissonant. The work was definitely not helped by having the main action spoken by actors, a disappointing decision since too much dialogue, here accompanied by the orchestra, simply shows up opera's weaknesses: better for the music to stop so you can concentrate on the dialogue and the acting. Or you could take the view that the spoken text pales in comparison to the sound of the singing voice - since, after all, we came for the music. Attended the European premiere of this work last night. Another masterpiece from the greatest living composer - and one of the greatest of all time.

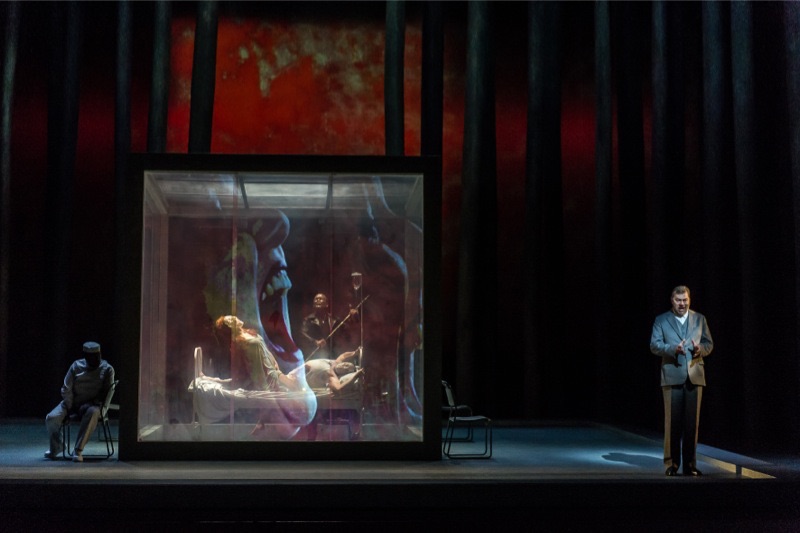

Eventually caught up with The Minotaur at ROH last night. I would hardly call it a pleasurable experience. The opera threw all sorts of other great things at me in abundance; but sheer pleasure was not one of them. Most operas give pleasure and have done so for ages; I guess the relentless atonality - and the largely declamatory style of singing that goes with it - conspired to deprive me of, well, operatic rapture. Why should this be so? And does it matter anyway? It certainly held my attention - it was compelling, awesome you might say - so it must have succeeded. But it was like beholding a brutalist piece of modern architecture which you somehow feel has been built by architects for architects, rather than for ordinary people to enjoy and marvel at. You can't deny the originality or scale of achievement. But it doesn't give you much pleasure.

Can't help but compare The Minotaur with A Flowering Tree (written within a year or two of each other). I reckon AFT would be reckoned by most as quite a 'difficult' modern opera, and in fact it seems TM has received more performances. Both works are original and up-to-date and inventive. But AFT has an additional dimension: the beauty of sound and of singing. Driving home yesterday, I caught some of the Royal Philharmonic Society's musical awards. I didn't hear it all and my attention was not complete, but I heard a good speech by the classical music popularist Gareth Malone in which he felt that the achievements of British musicians should be shouted from the rooftops. It wasn't particularly insightful, but he was passionate and spoke on behalf of the general music-lover, performer and teacher - all of whom need their advocates. The winners that were then announced are exciting practitioners of contemporary music and I would always find time to listen to their works and follow their progress wherever possible: I heard a choral piece by Jonathan Harvey, John Cage, a Ligeti Étude, and a song from a Spitalfields outreach project. But I couldn't help feeling that these examples would be impenetrable to the public at large. Even Abbado and Pollini receiving awards seemed irrelevant: what need do these masters have of more recognition? It all seemed to inhabit another world, where the difficulties of working with ordinary musicians and appealing to ordinary audiences seemed a million miles away.

Then, in the evening was the finale of the BBC Young Musician of the Year. I don't often like classical music on TV, but, switching on late, I was completely mesmerised by Laura van der Heijden's performance of the Walton Cello Concerto. It wasn't just that she was a consummate artist in every way (aged 16!) but also that her personality exuded wisdom and joy in equal measure. For once, this competition achieved a satisfying conclusion. There has been much talk recently of the drought conditions prevailing in this country which have recalled the severe drought of 1976. My memory is not always very good, but I can remember much about that year.

Recently caught up with the TV documentary Britten's Children. I want to question the values of purity and innocence which are so often quoted in connection with Britten's music. Why is some of his music considered pure? Some of it is indeed beautifully simple: he knows when to turn down the volume, when to stop writing notes and to let the words speak for themselves. But just because the music is song-like, or that children's voices are performing it, it doesn't necessarily follow that the music enters a realm of purity - to which other composers of all eras can only aspire! And for that matter, I don't buy into the notion of innocence either. Kids may be young and hopefully relatively care-free but they surely have strains and stresses - and tantrums! - like the rest of us. Just because someone isn't grown up (or may not have lost their virginity) doesn't mean to my mind that they're innocent, or in any kind of special blissful state: anymore than someone who is grown up (and experienced sexually) doesn't become 'guilty' or impure. I can't help feeling that in the background there's a lot of prudishness going on and, at the least, the view that innocence and purity are somehow wonderful involves looking at childhood through rose-tinted spectacles. Could this only happen in England?

Heiner Goebbels - this guy's music is so good, so individual; just listening to it again and it's going straight on my iPod. Check out Surrogate Cities and Landschaft mit entfernten Gewandten.

There's a debate at the Cambridge Union this evening on the motion 'classical music is irrelevant to young people'.

|

Edward LambertComposer and musician Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

|

Scores available by means of a Performance Restricted license from IMSLP

The Music Troupe

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed