|

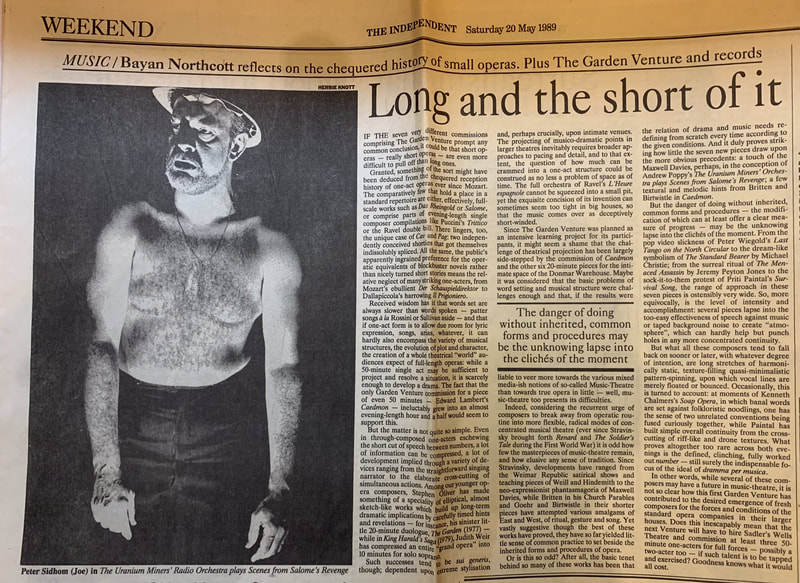

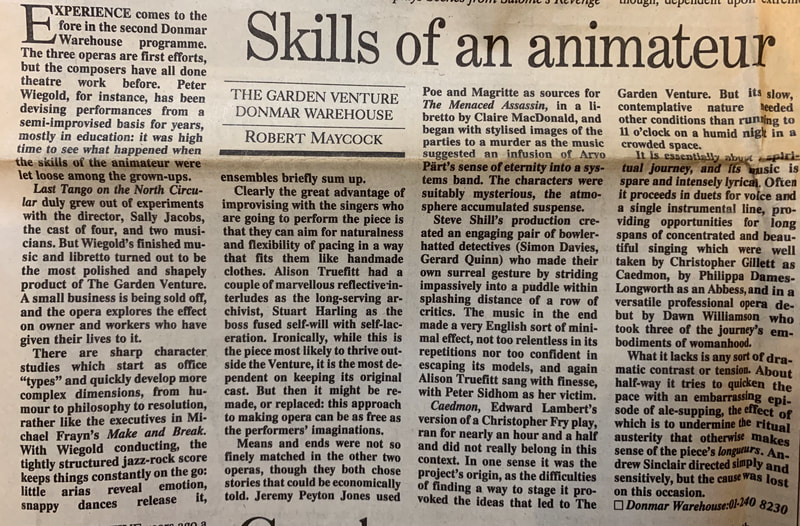

The recent death of Andrew Sinclair, international opera director, has suddenly brought to mind the period when he and I most closely worked together. The occasion was his direction of my chamber opera Caedmon, produced by The Garden Venture at the Royal Opera House in 1989. Some background is necessary. The Garden Venture was an initiative by two ROH staff members at the time, Wilfred Judd, a director and Kenneth Richardson, the opera company manager. Discussions had been flowing regarding the future of opera and, in particular, how to present opportunities for its renewal by new creators. I was part of the ROH community, and a composer too; I was also part of the flourishing outreach programme at the time and our chief mission during the 1980’s was to inspire and assist schools in making their own operas. I’d suggested the incorporation of a Royal Opera Van which would complement that programme by touring small-scale performances of new works. (Unlikely as it sounds, surely this should happen?) Be that as it may, some of these ideas came together and Wilfred and Kenneth got the go-ahead for their plan to produce a handful of new operas which were to be (if I remember rightly) each about 50 minutes long, four of them produced over two evenings in a mini-festival at the Donmar Warehouse around the corner. They had to find the money themselves: this would not be part of the House’s budget. In an extraordinary flight of imagination and initiative for the time, the young Independent newspaper agreed to host a crowd-funding scheme in which readers were asked to contribute £100 to support the Venture. It worked; donations flooded in. In the meantime, I’d been instructed to start work. But on what? At first, I had no ideas. I knew the kind of work I wanted to create but not its subject matter. Then one Sunday afternoon I heard a radio drama called One Thing More about the Anglo-Saxon poet Caedmon. That period in our history, Caedmon’s story derived from Bede and the writer’s lyrical treatment of it, stirred me into action. There was the small matter of the play’s creator who turned out to be Christopher Fry (who he? I asked). Enquiries through the BBC led us to approach him and I well remember the day Wilfred and I drove to the depths of East Sussex to visit him and persuade this wonderful elderly gentleman to allow us to mess with his precious creation. It has to be said, The Garden Venture wasn’t a success. I guess the blame lies with the fact that it was a ROH offshoot. Expectations were high, artists had to be paid properly, productions were costly. This wasn’t the umbrella for first-timers like me nor for experimental music-theatre makers. The Independent was bringing the full glare of publicity down on a handful of unknown composers lacking opera-writing experience. That was the point, of course, but full of pitfalls. In addition, as far as I can recall, the artists involved were all freelance outsiders. There were plenty of singers and musicians within the House .who would no doubt have been eager for some extra-curricular activity, but scheduling and contractual problems precluded that. So the one big advantage of the opera company - its personnel - wasn’t exploited. I was affected by a change at the top: with an eye on TV programming, newly-arrived Jeremy Isaacs influenced the commissioning of the composers by suggesting more operas with shorter durations of 20 minutes each. I’d been given a head-start with Caedmon and was by then half-way through its composition. How would my longer piece fit in with the rest? There were now seven composers and they decided to play four on one evening and three on the other. Caedmon was scheduled to start the 3-piece evening. Then my colleagues complained that Caedmon was too long and insisted on getting it placed last on the programme. That was ok by me - until I learned that their 20-minute pieces had actually doubled in length. With quite complex interval changes, that meant Caedmon didn’t start until nearly 10pm on the first night. This was, of course, before the advent of computer music technology and Caedmon had been hand-written on hundreds of sheets of manuscript laid out all over my floor to get a feel for its flow. (Stravinsky did this, apparently.) I hadn’t got it right. The first scene was over-long and I remember saying to Andrew after our first run-through that we should simply cut it. So this is how I remember Andrew Sinclair: the most sensitive of artists, fun and intelligent to work with, but also a man of steel. In no way would he consider this cut, or a cut of any kind. “But I’m the composer”, I pleaded. “It’s my piece!” “Well, you should have more confidence in yourself, Ed. Cut it, and my name’s removed from the production.” (Or words to that effect). I had no choice; the music remained complete and Caedmon perished late one summer’s night in a sweltering Donmar Warehouse. My two musical influences at that time had been Tippett and Ligeti. They may sound like strange bedfellows, but I admired Tippett’s free-rein imagination and I liked Ligeti’s technique in the way he strung notes together (apart from other things). My music, then, largely consisted of cluster-type sounds revolving around a note-centre which unravel to form chords. I believe now, and I believed then, that this kind of bi-polarity between dissonance and consonance is good for opera: it sets up a dynamic which is inherently dramatic. But the musical world was stylistically very self-conscious in those days. You were no good if you weren’t ‘modern’. One reviewer remarked that the music of Caedmon was influenced by Britten and Birtwistle (not too far off the mark) while another condemned it as being ‘out-of-date 80 years ago’. (How can two people hear so differently?) I’m not sure that anyone ‘got’ that Caedmon’s party scene was a medieval mock-up, The Widow sang a "Celtic folk-song" and the Abbess’s scene was a "renaissance motet". I guarantee that if Caedmon were revived in today's more eclectic era, stylistic cohesion would be the last thing on anyone’s mind. And yes, I subsequently revised the first scene, cutting it quite drastically. No praise can be too high for Wilfred Judd’s and Kenneth Richardson’s initiative back in the 1980’s. Against all the odds, they got The Garden Venture off the ground, even though it soon became flightless under its own weight. There were two or three more incarnations of the festival and many composers, writers, creatives and performers were given valuable opportunities. In my case, Christopher Gillett, who sang the role of Caedmon, went on to enjoy a long and successful international career - as, of course, did Andrew. It wasn’t until 25 years later that I re-surfaced as an opera composer: getting older, I had to get on with what I needed to do. Besides, the ideas started to come thick and fast, starting with Pirandello’s Six Characters, dramas by Lorca and collaborations with Norman Welch, Max Waller, Leo Doulton and, as I write, Christine Aziz. Meanwhile, the mantle of The Garden Venture has been taken over more successfully by Tête-à-Tête: The Opera Festival whose model is also more appropriate financially: visiting groups and companies provide the productions and how they pay for them is their business. Sure, artists are not paid well, if at all, and standards are variable; but the festival provides a sketch-pad for creatives to have a go, which is exactly what was needed in 1989.

1 Comment

17/3/2022 11:34:16

What an exquisite article! Your post is very helpful right now. Thank you for sharing this informative one.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Edward LambertComposer and musician Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

|

Scores available by means of a Performance Restricted license from IMSLP

The Music Troupe

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed