|

Have had a wonderful variety of operatic experiences recently and, while I’m always interested in the insights that different productions can bring to a work, I can’t help but reflect chiefly on the quality of the music-making and, even more, on how the composer problem-solved, setting text and underlining a drama by means of the singing voice. While not denying the cast and creatives their credit, nothing can redeem a bad score - whereas a good score can suffer if justice isn’t done.

0 Comments

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document. Your Editorial "The Guardian view on touring opera: thwarted in its mission to bring music to the people" (10 November) misses a vital point. The trouble with 'opera' is that it’s obsessed with a small canon of works almost exclusively from the 18th and 19th centuries. Exceptions are few and far between, while contemporary works, with their inherent risk, are as rare as hen’s teeth. And so opera isn't just perceived as elitist and expensive (mistakenly) but also as 'uncool' and irrelevant, especially by the young.

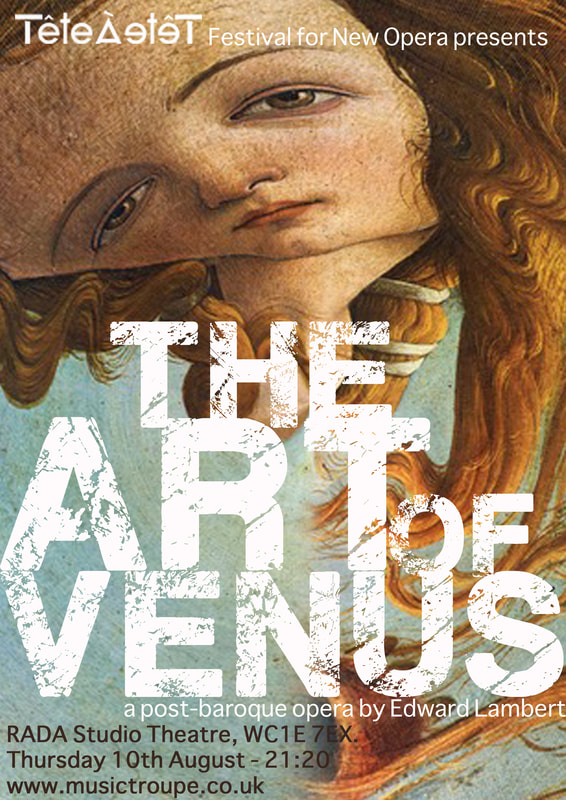

Scaled-down versions of those classic favourites don't come anywhere near an authentic experience and touring them has limited effectiveness in growing audiences. Those of us further down the ladder attempting to mount new opera on a very small scale face a huge battle with conservative audiences, limited funding (no encouragement from the Arts Council there) and apathy from colleagues and influencers in the industry: all seem to be stuck in the operatic past. Without a sustained and sustainable renewal of the genre, however, the myth of opera's obsolescence will become a reality. So we need more lithe and nimble regional touring companies which can afford to mount new operas and thereby enhance cultural life more widely - and in more senses than one. It's perhaps the Royal Opera's Linbury Theatre, with its varied offerings of opera and dance, new and old, which could and should plant regional off-shoots. ENO should stay put. www.theguardian.com/music/2023/nov/13/its-a-shame-that-opera-remains-stuck-in-the-past https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/nov/10/the-guardian-view-on-touring-opera-thwarted-in-its-mission-to-bring-music-to-the-people? It seems to me, the year begins anew after the shortest day. However, with all the reflections on FB today, I’ll throw in my thoughts on a busy and peculiar year of musical composition. This time, 12 months ago, I was working on Swellfellow the Tyrant, an obscure political satire by Shelley which could hardly have turned out more topical and relevant in the light of the subsequent Tory machinations. Written for a local opera group which then failed to grasp the nettle, they thought it wasn’t popular enough to rustle up support. A foolish sentiment, in my opinion, as opera won’t thrive going forward unless the repertory is renewed with small-scale, entertaining but relatively economical works. An opportunity lost to work in the local community. And so, straight on to write The Burning Question for young Norman Welch which didn’t start off with the idea that the dead pope should be female, but that’s how it landed up. It went down pretty well at the Tete a Tete Opera Festival in the summer - lots of young people there - and, as I write, there are plans to revive it soon. Probably the best team effort I’ve enjoyed working on: it’s so satisfying (and flattering) to see a talented cast throw themselves into something you’ve written. Four months later, and another piece is finished: Masque of Vengeance, this time a Jacobean tragedy, a bloodbath in which most of the comparatively large cast are slaughtered by the end. I really must try and understand why, after Elizabeth’s death, this genre of revenge tragedy flourished. Wait! I meant Elizabeth I…! And in between we released the film of Last Party on Earth, which we shot live on a set and on location during lockdown. There aren’t many opera films other than relays of house performances, so thanks to Korina Kokali et al. for the inspiration. All things considered, some steps in the right direction this year: as one acorn said to another, we may be small but we’ll give it a go!

Mark Wiggleworth’s suggestion (The Guardian, 10 Nov 2022) that English National Opera should seek a new state-of-the-art lyric theatre is spot on. The trouble with the recent debates over the future of English National Opera has much to do with the term ‘opera’ covering over 400 years of works that come in all forms, shapes and sizes. For much of that time, companies and the houses that accommodated them, were smaller and more intimate. Some of us mourned when Sadler’s Wells Opera moved to the Coliseum in 1968 in order to expand into the Wagner/Puccini/Richard Strauss repertory, for in large spaces something is lost when performing works of previous periods. While applauding ENO’s many great achievements since then, particularly as a showcase for U.S. composers, a retreat into a smaller, purpose-built venue in London could see it flourish as a complementary company to the Royal Opera rather than one competing with it. Smaller productions would be more suitable for touring, too. There is also an important point to be made about the future survival of opera: the repertory must be renewed with contemporary works in sufficient quantity to allow new creative talent to flourish. This is much more likely to happen in a small-scale environment.

Orpheus at Opera North: greater than the sum of its parts

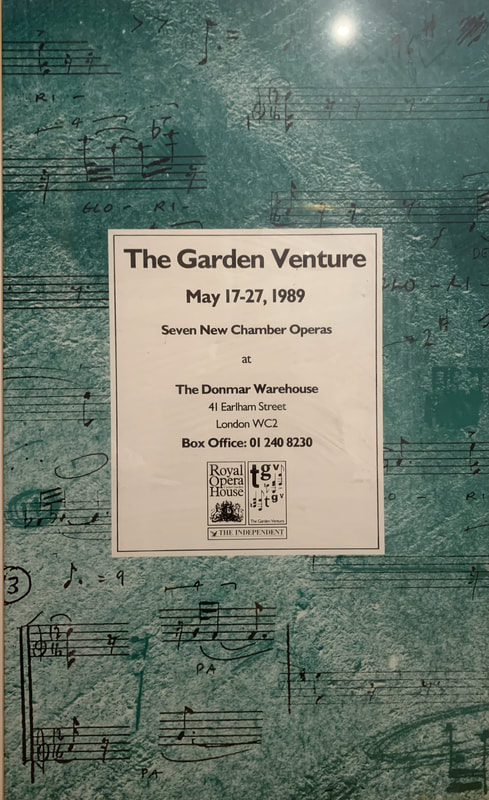

(Grand Theatre, Leeds, Thursday 20 October 2022) The myth of Orpheus was fundamental to the history of early opera: Peri’s Euridice is the earliest surviving opera and its performance in Florence in 1600 was attended by the Duke of Mantua - Monteverdi’s employer - and Alessandro Striggio, who would write the libretto for Monteverdi’s opera of 1607. The attraction of the myth, of course, was that the story was widely known and understood; Orpheus, as a musical practitioner, becomes a parable for the genre of opera itself, a union of words and music which gives voice to this drama about love and loss. No wonder composers have struggled with the myth’s ending, sometimes tragic, sometimes happy, and sometimes, as with Monteverdi’s later drafts, somewhere in between. The recent death of Andrew Sinclair, international opera director, has suddenly brought to mind the period when he and I most closely worked together. The occasion was his direction of my chamber opera Caedmon, produced by The Garden Venture at the Royal Opera House in 1989. Small-scale opera is a thing nowadays, not surprising given the economies involved. Lots of popular classics have been doing the rounds - La Boheme, Carmen, La Traviata, G&S, etc., as well as arrangements of less mainstream works. Anything to get opera out and about and attract new audiences everywhere is to be greatly applauded. But it has to be admitted the resulting musical experience without orchestra and choruses is likely to be underwhelming compared to the experience that was intended. Just as we like ‘Early Music’ to sound right with period instruments, so grand opera ideally needs to be savoured as the ‘real thing’, performed by the forces and in the spaces it was written for. But it’s worth noting that theatres in the 17th and 18th century (1000 seats) were nowhere near as large as those built in the 19th century (around 2000 seats) - and these are dwarfed by the monster new-builds and extensions of the 20th (3000 to 4000 capacity). In these auditoria, most spectators are distant from the stage, many spy on the performance through opera glasses and typically listen with acoustic enhancement (amplification) even if they’re not aware of it. By contrast, small-scale opera in intimate venues allows the audience to feel close to the stage and feel more involved in the drama. Clearly, voices don’t need to be so large (and wobbly) and don’t have to strain; they can, more often than not, sound more detailed and beautiful. The challenge we face, therefore, is to create new, tailor-made, small-scale works that appeal to audiences everywhere and enhance the repertory of sung dramas that are so powerful and compelling.

A project in the autumn and winter lockdowns recently has been to finish another Lorca setting. My operatic version of Así que pasen cinco años I've called In Five Years' Time, which seems a more natural translation than 'When Five Years Have Passed'. Death is a theme of the play and very much in the headlines right now.

Written before the pandemic outbreak, this could hardly have been more timely. A rhyming libretto by Leo Doulton at first had me stumped: how could such a doom-laden scenario be treated as a 'comedy of manners', as he put it?

I went to see Music Theatre Wales' production of The Golden Dragon in Basingstoke recently. This is a production which has caused some controversy because of its ‘yellowface’ casting.

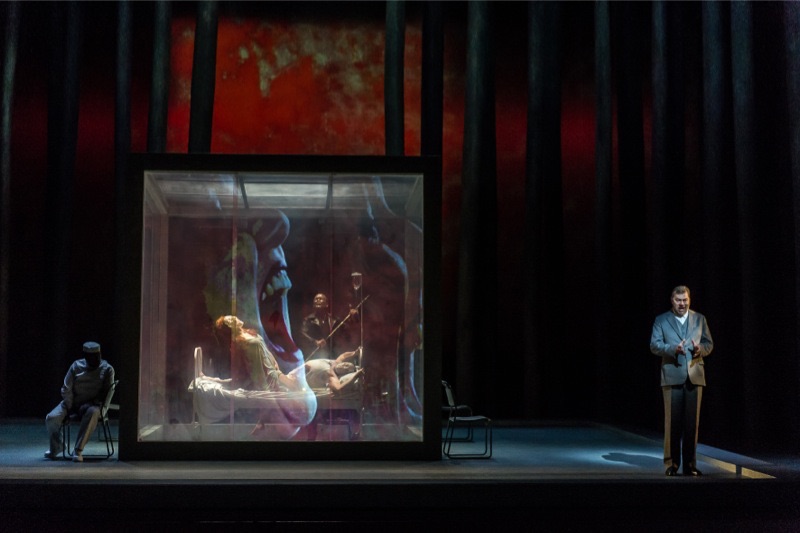

Attended a performance last night of Le Grand Macabre at the Barbican, London. An immensely good performance and riveting from start to finish. It was great to have the London Symphony Orchestra on stage, which meant we could relish the score's fabulous textures which bristled and shimmered and hooted and blasted and everything in between.

A single remaining, inexpensive amphitheatre seat tempted me to venture to Die Frau ohne Schatten at the Royal Opera House yesterday afternoon.

Recently attended an operatic relay from Royal Opera House in the local cinema. Heard much about these events and wanted to experience one for myself, but I have to admit I was dreadfully disappointed.

I must catch up with some more operatic experiences this year: there was Glass' A Perfect American, whose music was much less absorbing than that of Akhnaten or Satyagraha and whose subject was not very interesting. If Walt Disney had no redeeming qualities, how was the opera going to yield any insights into the human condition? Apart from an entertaining production, the work itself seemed pointless.

Lohengrin in Cardiff was visually depressing - a nineteenth century prison? - but the music won out in any case. Brought back many memories of one of my first tasks at the Royal Opera House when I joined the staff there: coaching the chorus was hampered by constant strikes in those medieval, pre-Thatcher times and it was touch-and-go whether the music could be learnt in time. No such worries with WNO - the chorus were spectacular and so were the cast and orchestra. The clarity and directness of the music when performed well like this are very refreshing in comparison to Wagner's later works. Wagner Dream by the late, great Jonathan Harvey was, unfortunately for me, impenetrable. Multi-layered, complex and very dissonant. The work was definitely not helped by having the main action spoken by actors, a disappointing decision since too much dialogue, here accompanied by the orchestra, simply shows up opera's weaknesses: better for the music to stop so you can concentrate on the dialogue and the acting. Or you could take the view that the spoken text pales in comparison to the sound of the singing voice - since, after all, we came for the music. Eventually caught up with The Minotaur at ROH last night. I would hardly call it a pleasurable experience. The opera threw all sorts of other great things at me in abundance; but sheer pleasure was not one of them. Most operas give pleasure and have done so for ages; I guess the relentless atonality - and the largely declamatory style of singing that goes with it - conspired to deprive me of, well, operatic rapture. Why should this be so? And does it matter anyway? It certainly held my attention - it was compelling, awesome you might say - so it must have succeeded. But it was like beholding a brutalist piece of modern architecture which you somehow feel has been built by architects for architects, rather than for ordinary people to enjoy and marvel at. You can't deny the originality or scale of achievement. But it doesn't give you much pleasure.

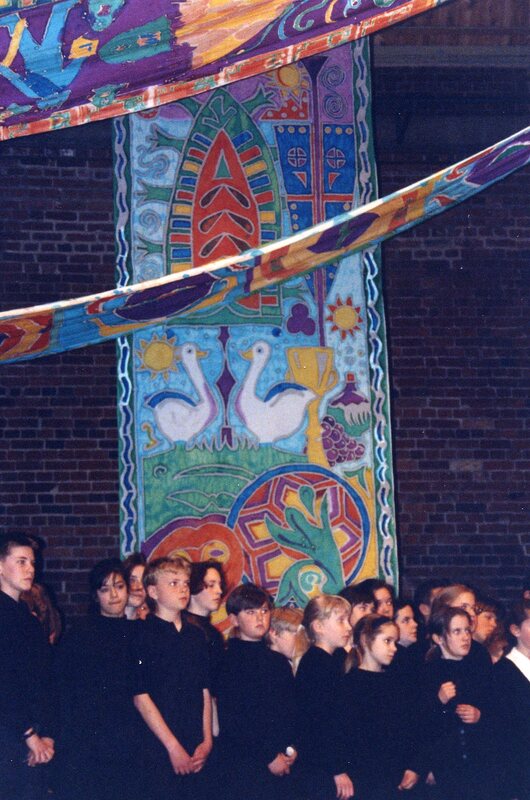

Can't help but compare The Minotaur with A Flowering Tree (written within a year or two of each other). I reckon AFT would be reckoned by most as quite a 'difficult' modern opera, and in fact it seems TM has received more performances. Both works are original and up-to-date and inventive. But AFT has an additional dimension: the beauty of sound and of singing. The Treasure and a Tale tells the stories of Beowulf and the discovery of an Anglo-Saxon ship burial and its treasure at Sutton Hoo in 1939.

Suitable for school or community performance Although conceived as musical theatre, the emphasis is on telling the Beowulf story through rhythmic recitation accompanied by drumming. With the exception of the Gleeman, who has a challenging solo part, the singing roles are introduced by way of reported speech and so may effectively be taken by everyone acting as Storytellers. By way of contrast, the scenes are separated by spoken interludes which tell of the finding of the treasure in Suffolk against the background of World War II, sketched briefly through the eyes of local children and an evacuee. There is, of course, no direct connection between Beowulf and the treasure from Sutton Hoo; yet they have in common the society that created them and each brings the other vividly to life. |

Edward LambertComposer and musician Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

|

Scores available by means of a Performance Restricted license from IMSLP

The Music Troupe

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed